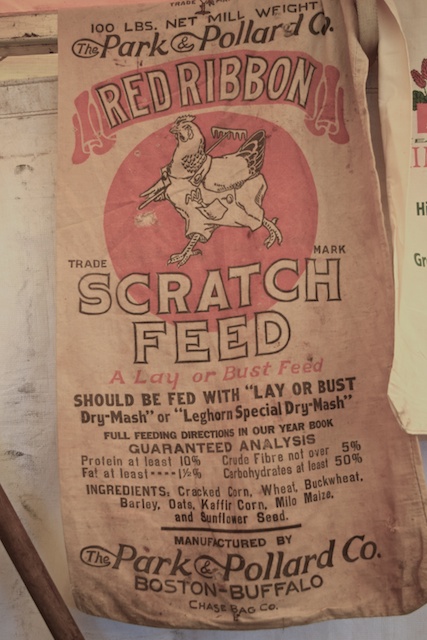

A lot of poultry books and backyard chicken enthusiasts on the web make it sound as if all you need is a small box in which to house your hens. Their advice isn’t new. I have a pamphlet from the 1920s illustrating how to make a chicken coop from a piano crate (back then upright pianos were wildly popular and their shipping containers were as prevalent as pallets are now.) However, in the past, it was understood that these coops were designed for keeping chickens through one laying season, and then they were harvested for meat. If you want to keep your chickens healthy and content for any longer than that you’ll need to install a coop of a better design.

Most modern coops are too small, and have too few windows. Sunlight is essential for the well-being of your hens. But more on those criteria in another post! This one is about ventilation, which is essential to prevent respiratory disease and for keeping your flock healthy. After this past winter of the polar vortex, many people discovered just how inadequate their coops were. Flocks that never before got frost bite saw damaged combs. In every case that I heard of, the frozen combs could be linked back to inadequate ventilation.

Chicken manure is 75 to 80% moisture. Additionally, when chickens breathe, they expel moist air. Damp air holds germs and viruses and causes respiratory ailments. Additionally, when manure breaks down, ammonia fumes are released, which, when breathed by chickens (and humans) can cause respiratory distress. We’re well aware of this in the summer, when the coop smells bad and the air feels humid. But, in the winter, most chicken keepers don’t worry about damp air because the coop feels dry when the weather is frigid. Although the air doesn’t feel heavy, it has its own problems. It sounds counter-intuitive but when air is cold, it can’t hold moisture, and so the damp stays where it is near the floor, and doesn’t move with the air out through the vents. Large-scale poultry operations understand the science of air flow.This is one reason that commercial barns are heated – to move the moist air out. For many reasons, I don’t like heat in the coop. Instead, I want a coop designed to be healthy for my hens regardless of the weather.

In the winter, not only is the air not efficiently carrying moisture out, but often people make the mistake of closing vents to keep the coop warmer. (Commercial operators heat the air, but they also keep the vents open!) Sometimes the coops are so badly designed that vents/windows must be closed during inclement weather. Additionally, I’ve seen coops so low to the ground that they get covered in snow, effectively insulating them, blocking air exits, and preventing any ventilation. Your coop must have ventilation that can stay open, even in the worst of storms and in below-freezing temperatures. Yet, at the same time, your coop shouldn’t be drafty. Getting this balance right is the trick.

There’s a reason that old barns have cupolas – they’re perfectly designed for year round ventilation. My Little Barn has one. That charming cap on the roof is actually a working vent that pulls air up and out. It keeps the coop cooler in the summer, and air circulating in the winter. Fresh air comes in through the pop-door and goes up and out through the cupola.

But, in the winter, knowing that the poop is holding onto its moisture, I also keep the barn skipped out (a nice horse management term for removing manure frequently.) Only during blowing snowstorms do I close the pop-door. Otherwise, it stays open, even during the coldest of days, to bring fresh air in. (I do lock it closed at night to keep predators out.)

Vents along eaves rarely move enough air. Some small coops have ridged roofs, which supposedly provide for plenty of ventilation. (This coop was found on PInterest; there was no link.)

However, I know someone who built a coop similar to this and this past winter her hens had frostbite. The problem here is that there isn’t enough headroom. The chickens roost right near the ceiling, right next to the venting. Cold air flows right over their combs. I wouldn’t be surprised if, at night, with the pop-door closed, that air flowed in instead of out.

On the other side of the weather spectrum, a chicken keeper has to worry about heat, which is far more dangerous to your birds’ health than cold. However, once again, good ventilation can go a long way to prevent problems. It was in the 90s the day that we installed the cupola in the Little Barn, and as soon as the hole was cut into the roof, the temperature inside of the coop dropped 20 degrees. If possible, have cross-ventilation. Windows are good. For those days when the it’s brutally hot and humid, I run a box fan to move the air. If in doubt, put a thermometer inside of the coop. Those small box coops, sited in the sun, can become ovens without you realizing it.

So, knowing all of this science of moisture transfer, and damp manure, what should a small coop look like? I have a FAQ with coop design criteria here. For ventilation, and for many other reasons (including behavior issues), the best coops have a minimum of 4 square feet per hen (not including nesting boxes if they’re built into the floor, nor outside pen space.) They should have windows that let in plenty of sunshine. Roosts need to be a good 18 inches or more up off of the floor – I prefer a ladder roost that is several feet high. Air space is as important as floor space! If the roof has a vent like the one pictured above, it shouldn’t be right at the top of the roost, but well above the sleeping hens’ heads.

Too often, people like the idea of having the smallest coop possible. When planning shelter for your chickens, reverse that idea. In the case of hen housing, bigger is better, Still, I understand about space constraints and have an annotated Pinterest page with small coop ideas.

If you’ve had problems with ventilation, let me know. If you’ve solved those problems, I really want to hear about it!