A hen eats about 4 ounces of food a day, and lays an egg that weighs 2 ounces. What goes in is what comes out. The quality and the ingredients of the feed matter. Raising your own chickens for eggs means that you know what your hens are eating. Chickens are omnivores and thrive on a varied diet, but they also have exacting nutritional requirements in order to be able to convert what they consume into eggs. I’ve written about what to feed chickens here.

Some people believe that blending their own mixture from individual ingredients guarantees that their hens will be consuming the very best provender possible. After all, they think, it’s not as processed as the commercial pellets. But, for many reasons, homemade chicken feed is problematic. First of all, it’s difficult to keep homemade feed fresh for a small flock because much of what goes into a ration for layers contains oils, and so turns rancid if it is stored for too long or improperly. Also, hens are picky eaters. If fed a mixture of loose grains, the hens will ignore the bits they don’t like – often eating only the carbohydrates and leaving the protein. Or, they’ll gorge on seeds and get too much protein. The homemade ration will separate – the lighter and smallest pieces will fall to the bottom. What your hens eat won’t be balanced. This also happens with commercial blends that are not pelleted, but that are composed of whole and cracked grains – I’ve heard of many ailments that arose from nutritional imbalances that occurred when grain mixes, not pellets, were fed,

My flock is fed commercial laying hen pellets. This ration is nutritionally appropriate, and it’s in a form that isn’t wasteful. It’s easy to purchase and easy to store. I understand that many people, having decided to opt out of the industrial agricultural model, would also like to opt out of buying chicken feed made by Nutrena (Cargill) and Purina (Nestle). I see this as a personal and political choice. Sometimes you don’t have an option – rations made by the big corporations might be all that is available. It might be what you can afford. Your hens will do fine on it. But, those big players aren’t the only ones making chicken feed. There are regional feed mills, like Poulin Grain. I recently asked Poulin if I could come up and tour their plant. I wanted to know exactly what goes into their feed and how it is manufactured.

I arrived on a snowy spring morning. It was a long, but beautiful drive to get there. The mill is in Vermont, on the Canadian border.

I met Josh Poulin, the fourth-generation of his family to run the mill (his sister is also involved.) Scott Birch, the Quality Assurance Manager, gave me a tour. It’s a busy place. They make a variety of animal feeds, including dairy rations, rabbit pellets and horse feed. Poulin manufactures 35 tons of laying hen pellets daily. (Which is a small amount when compared to the major feed corporations.) The plant runs around the clock – 24 hours a day.

Feed arrives by rail and truck.

It comes in from the Canada and the midwest. Much of it comes in a milled form. There is storage in classic silos.

Milled grains are accessed from these bins. There is a fine dust from the light, soft grains, which covers every surface, but the facility is tidy and smells clean. The Poulin feed does contain soybean meal. It is a readily available, digestible, and affordable vegetarian protein.

There are conveyor belts everywhere to move grain from one place to another.

Some ingredients arrive in bags.

Poulin laying hen pellets include three essential oils, obtained from oregano, cinnamon and chili peppers. These help to keep poultry healthy without the use of added antibiotics (as is often seen in industrial agriculture.) They also add a product called Bio-mos which takes on a role similar to probiotics – it reduces bad gut bacteria and increases the good, which in turn promotes feed efficiency and health.

Because grain varies in its nutrient content, what comes in is analyzed in their lab. A computer takes that information and determines exactly how much of which grain goes into the product. The finished feeds are also periodically tested to ensure that the ingredient analysis on the label is accurate.

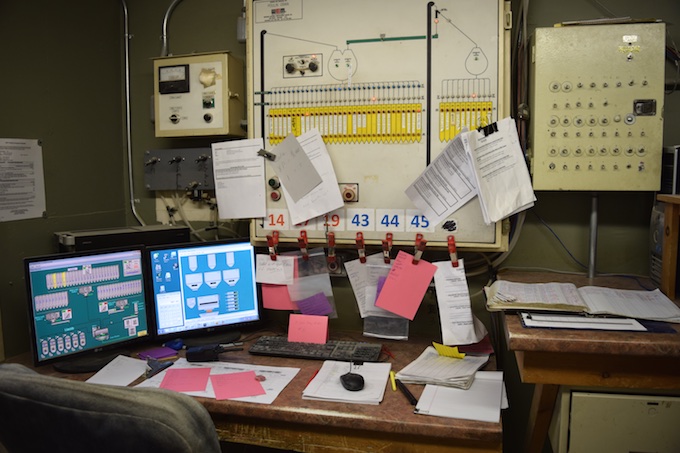

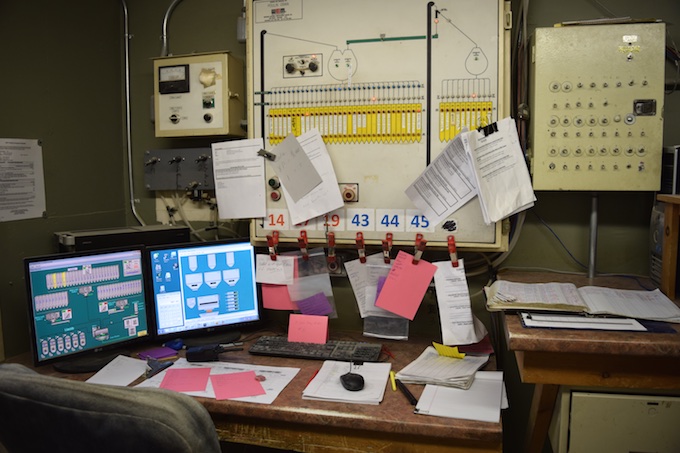

Each ingredient is measured on digital scales. It’s then sent on through the feed-making machinery. This is all controlled at a central computer. When I visited, Jason was orchestrating this complex job. Jason grew up on a local dairy farm. His family still milks cows. He cares about what goes into the feed.

The ingredients get mixed in hoppers.

Some of the machinery relies on gravity. I climbed many stairs.

Once the ingredients are mixed, the feed is pushed at high pressure through the pelleting wheel. This is what it looks like.

It is in this machine.

The grains are not cooked, but heat is generated as the pellets are forced through the molds. Nutritional value isn’t affected, however starches do gelatinize. There’s a tad of water, vegetable oil and binder added to the mix, but mostly the pellets hold together because they are compressed as they are extruded through the holes.

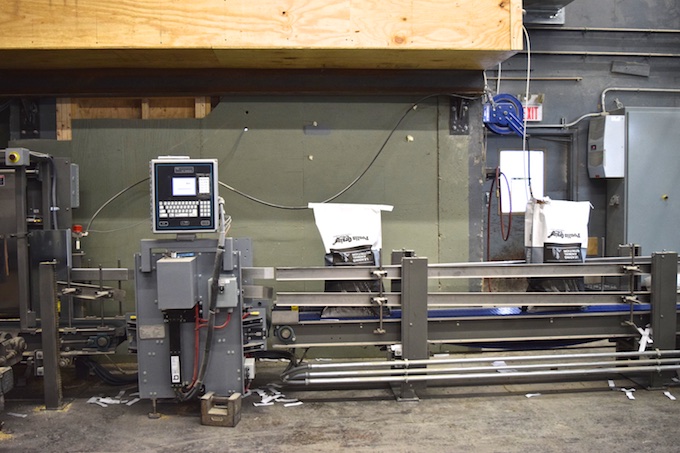

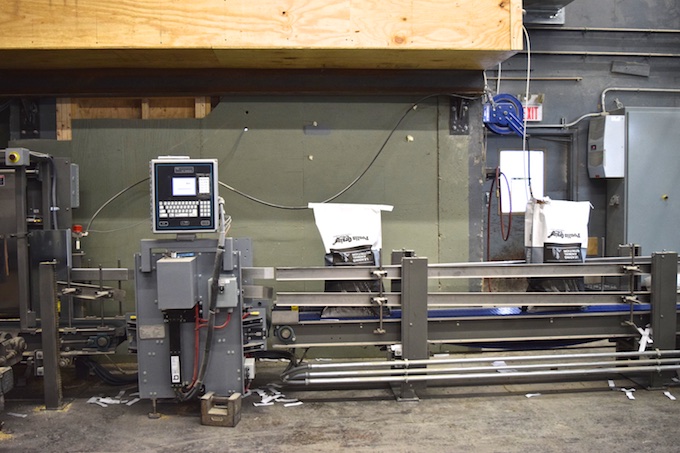

The pellets then get bagged. (This machine is getting replaced soon.) By the way, the only difference between crumbles and pellets is that the crumbles are broken into small pieces before bagging.

The bags are then put onto pallets and moved into the storeroom. There isn’t room to keep it around for long. It’s gone within days, but Poulin guarantees the quality for three months.

The whole place was a bit like a Rube Goldberg machine. So many complicated parts to make what seems like a simple product.

It might look boring to you, but my hens find it quite appetizing!

Note: The ads that you see on my website are put up there by Google Ads. I get a small amount of income from them. I have no control over their content. However, there is a Poulin Grain advertisement on my What to Feed Your Chickens FAQ. Because I feed Poulin laying hen pellets to my flock, I asked them if they’d like to place a banner advertisement on that page. I appreciate both their product and their financial support of what I do here at HenCam. I asked Poulin if I could visit their mill. I did not get paid for this blogpost.