It’s very difficult, as the keeper of a small and varied backyard flock, to make an accurate diagnosis about most health issues. Hen standing like a penguin? It could be cancer. Or she could be constipated. Rattly breath? Respiratory disease (and there are many) or ascites, or peritonitis. Or she swallowed a bit of straw wrong and will be fine by evening. If you’re looking for answers and go to an on-line poultry forum you’ll get a lot of misinformation, rehashing of Damerow’s books, and maybe some good tips, if you can sort the useful from the bad. There are plenty of blogs out there long on advice, but short on actual experience with the diseases they’re talking about.

When I’m faced with an issue with my girls that I need to know more about, I turn to Veterinary manuals, scientific journals, poultry industry research and fact sheets put on-line by Extension Departments (United States and Canadian agriculture colleges have these outreach offices to help farmers). I’ve gleaned much enlightening information from these sources, but it is not always applicable for my situation because all of the research is done on young, commercial flocks, and the protocols and advice given are for farmers, not a suburban chicken keeper who dotes on her old hens. As one extension fact sheet stated, layers are usually kept for 52 weeks. My Gems are 110 weeks old. Twinkydink is 416 weeks old. To poultry scientists, these birds don’t exist.

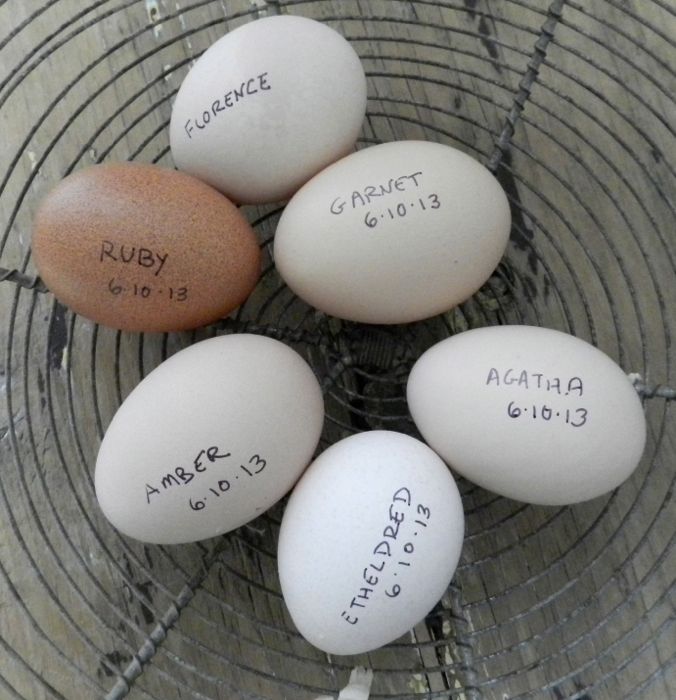

When researching what might be going on that the Gems are laying eggs with ridges, crackles, and rough surfaces, I came across photos of eggs that exactly matched what I’m finding in the nesting boxes. This photo from Cornell (scroll to photo # 5 of 8) matches Florence’s egg. These photos match the other eggs that I’ve been blogging about. The culprit appears to be infectious bronchitis (iB). On a production farm, with pullets of one breed, crowded by the tens of thousands inside buildings, this can be devastating. Birds will exhibit severe respiratory symptoms. Egg production will drop to near to nothing for up to four weeks. Eggs that are laid will be large and thin-shelled. iB is caused by a virus. There is no treatment other than time. Eventually the symptoms will pass, normal eggs will be laid, and the farmer will have to add up the financial losses. At 52 weeks all of those layers will be slaughtered, the housing disinfected, and the farmer will hope not to see this in the next group.

My Gems might have iB, but they never showed respiratory symptoms, egg production has dropped by only 10 % and less than half of the flock are laying odd eggs. Is this because older chickens some have immunity? Pullets on production farms are under a huge amount of stress. Perhaps that’s why entire flocks on factory farms succumb so severely. I have no way of knowing.

Or, perhaps my hens are carriers of another virus, one that causes Egg Drop Syndrome. Unlike iB, the affected flocks don’t show respiratory symptoms. They do lay eggs with shells the texture of sandpaper. Only one of my hens does that. Wild birds carry this virus, so perhaps that’s how it got a foothold here. Again, there’s no cure other than time. Since these viruses only affect birds (iB afflicts only chickens) the eggs are safe to eat.

If I were a commercial farmer, I’d follow the recommendations and slaughter all of the birds, disinfect, and begin anew. I’d also pay for lab tests to accurately identify the pathogen. But, I am not a farmer. I’m not even trying to have a sustainable homestead. As someone who keeps old chickens, I already accept the fact of life that egg production peaks at the first year, and goes down from there. I’m fine with a few less eggs because of this virus. I am not going to keep my chickens indoors away from all wild birds and possibly infected soil. I like to think that the healthy, less stressful housing, with fresh air and sunshine that I have here offsets the downside of possible exposure to pathogens. Since viruses lurk in damp and dust, I am obsessive about keeping my coop clean and dry.

I am concerned about the thin-shelled eggs caused by the virus. Thin eggs are already a problem with my older hens, simply because as chickens age they are less able to metabolize calcium for egg production. Fragile shells can lead to laying issues, including breakage and infection in the hen, impaction, and the bad habit of egg eating. I will have to be especially vigilant about collecting eggs frequently, watching for laying discomfort, and feeding a balanced diet to promote the sturdiest eggs possible.

I have a feeling that these viruses are prevalent in home flocks, as one of the most emailed questions that I get is about odd eggs. I think that most of us with older flocks live with some level of infection. The viruses do not survive long in fresh air, but still, I think about biosecurity. I am already careful not to wear barn shoes and jackets when visiting friends with flocks, and I ask them to do the same when coming here.

So, once again, I have to fall back on common sense and experience. I think that I’ve struck the right balance here, but I’m always learning. I’ll keep you updated.