It’s gross and you don’t want to think about it, but chickens have nasty parasites inside of them. There are various types of roundworms, tapeworms and flukes that live in the intestines, the eyes, the throats and the gizzards. A chicken with a heavy parasite load shows a loss of vitality, fewer eggs and a lowered disease resistance.

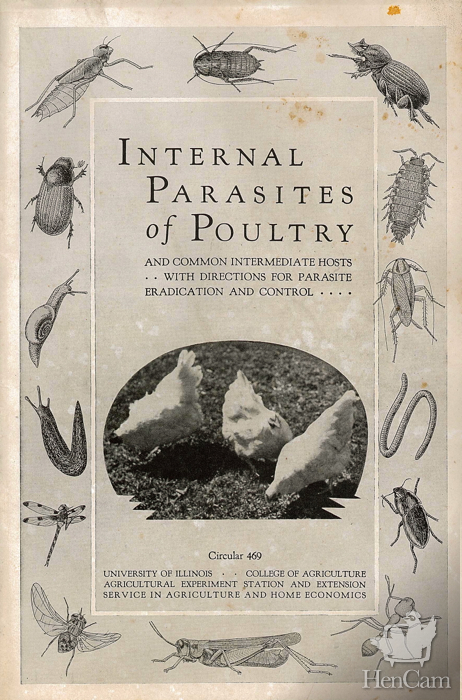

I’ve been researching and reading about this, both on-line and in books. But perhaps the best advice I’ve seen has come from this 1941 booklet.

The good news is that the parasites that live inside of poultry are avian-specific. They don’t live thrive inside of people. They don’t live inside of dogs. The parasite starts in one bird, and then its eggs are expelled in the manure, which are ingested by intermediary hosts (usually some type of insect that chickens find yummy) which then get eaten by another chicken. And so the cycle continues.

If you build a coop in your suburban backyard that hasn’t seen a chicken in 50 years, then it’s unlikely that for the first few seasons of hen keeping that your birds will harbor any parasites at all. Eventually, though, the parasites will come in via wild birds. Or maybe you’ll visit a friend who has chickens and you’ll get mud (and the parasites’ eggs) on your boots. Maybe you’ll pick up a bird at a sale. Eventually parasites will lurk on your property. But, that doesn’t mean that you have to dose your chickens with drugs. Management is the key to keeping your chickens healthy.

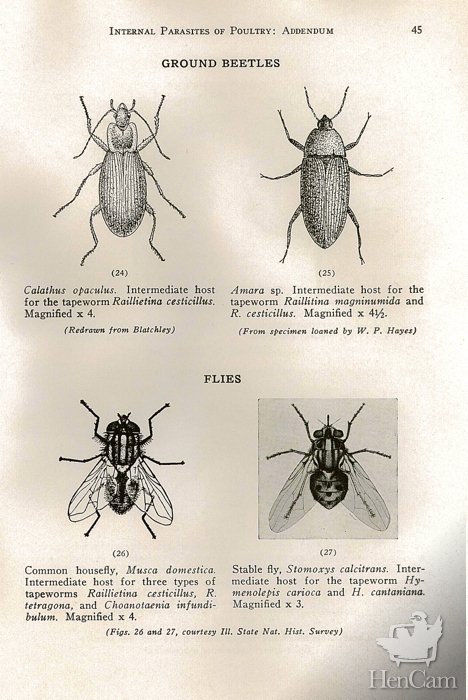

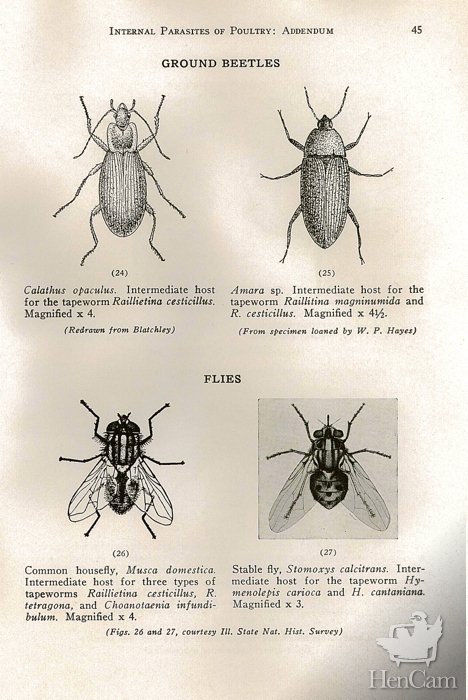

Notice how the cover of the brochure shows only one worm, but many intermediary hosts. That’s because it’s those common insects that are the key. Get rid of those hosts to break the cycle and your flock will be fine.

Beetles and flies need warm, moist and dark environments to breed. Eliminate those from your coop and pen. Also, the quicker you remove manure, the less time the eggs have to transfer into the ground and into the hosts. Rake it up. Compost it away from your flock.

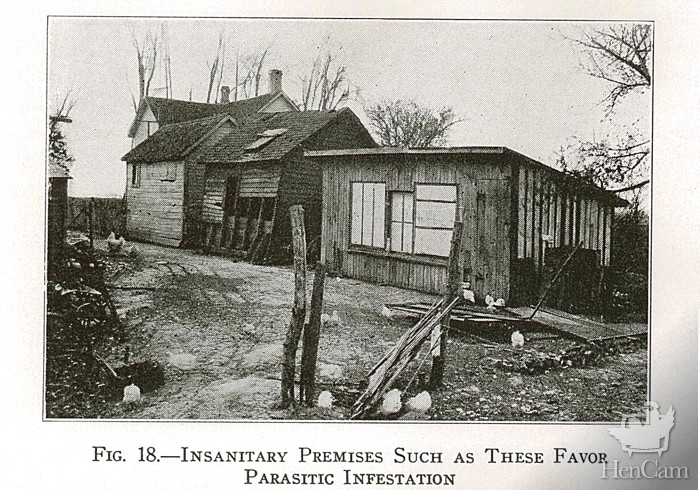

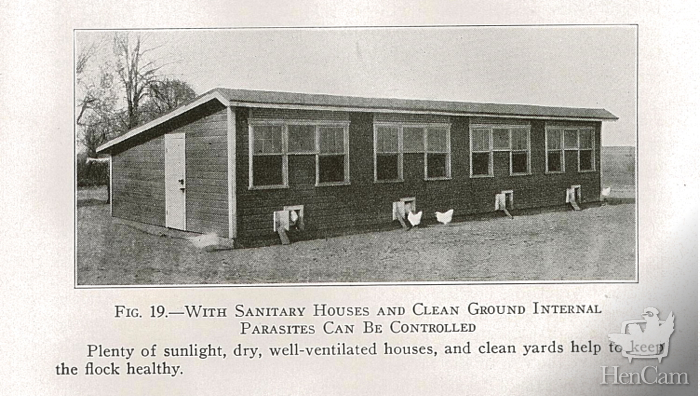

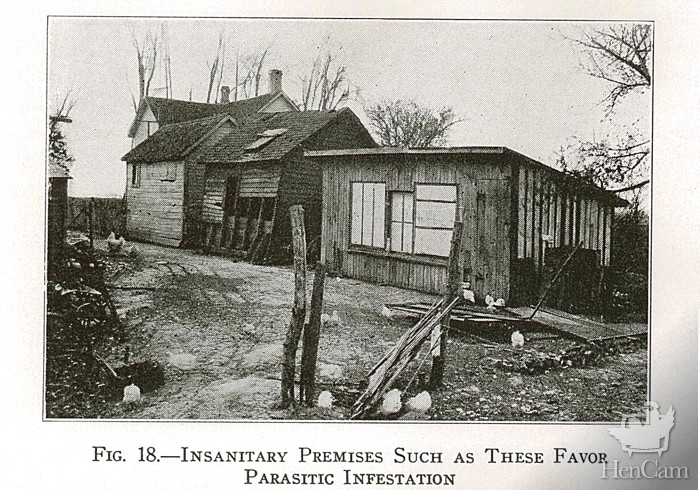

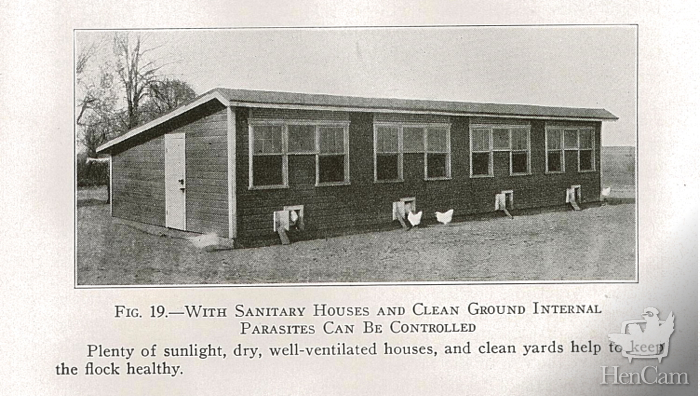

This pamphlet shows quite clearly the difference between a sanitary coop and a parasite breeding ground.

Keeping coops tidy isn’t just for appearances. It will also keep your hens healthy.

Every few years I take a fecal sample to the vet to test for worms. Only once did it come back positive for tapeworms. At the time, my chickens didn’t show symptoms and I never saw bits of tapeworm in the manure. Chickens are naturally resistant to parasites. So, I did not run out and purchase a chemical wormer. I did get rid of the pile of damp hay that the chickens were scratching in. I did start removing all of the manure daily from the coop and pen. I haven’t seen a hint of internal parasites since. (This is confirmed by the fact that in the several necropsies that I’ve done, that I’ve yet to see a single internal parasite.)

Some people worm on a regular basis. Some use febendezole, (known as flubnavet in the UK) which is the same thing as Safeguard horse wormer. It is not approved by the US government for chickens. Others use wazine, which is approved only for young stock and not for laying birds. Wazine is only effective on roundworms. The problem with regular worming of either of these, is that parasites develop resistance to drugs, and when you really need the chemicals to work, they will no longer be effective. I’m not minimizing the real problems that many flocks have with parasites. This pamphlet stated Internal parasites are the most widespread cause of poultry maladies. It also stated Sanitary management is the most effective weapon against these flock enemies. In 1941, Febendazole had yet to be invented. But, I’d still say that management is the first and best step. The chemicals will work once. Maybe twice. But, as we’re seeing with overuse of antibiotics, they are not a longterm solution.

There are so-called organic parasite controls on the market, herbal and otherwise. I’ve yet to see a study that showed that flocks infested with parasites saw an elimination of the problem with these products, but perhaps they are a worthwhile preventative. I’ve never used them so can’t vouch either way. Some claim that pumpkins are a preventative. Likely, it’s a chemical in the seeds, but getting the right amount in year round is not practical. Still, pumpkins are good for other reasons, so during pumpkin season it’s worth letting the hens eat them. I believe in providing food-grade diatomaceous earth in my hens’ dust baths to control external parasites. This might also help to control internal parasites. In any event, the natural supplements can’t hurt, but they aren’t a replacement for good management.

But, what happens if you do have an obvious, serious infestation? What if you see worms in the manure and your chickens look poorly? The first step is to do everything that you can to prevent re-infestation. If it’s possible to do so, move the run so that the birds are on fresh ground. Give your flock sunlight and dry earth. Tidy up the barn so the the black beetles have nowhere to hide. Remove manure. Dry up the manure pile with lime so that flies can’t breed. At the least after all of this effort, you’ll have the nicest looking, freshest smelling chicken yard around! But, if good management doesn’t help because the parasite load is too heavy, go ahead and use the drugs. Hopefully you’ll only have to dose once.