The molt is a part of the chicken’s lifecycle. Once a year a hen drops her old feathers and replaces them with new ones. The first time a chicken molts will be somewhere around 18 months of age, so most first-time chicken keepers are surprised when their glossy, full-feathered hens suddenly have bare spots and stop laying. For new chicken keepers, the reaction is often panic. Surely, a scruffy, grumpy, non-laying hen can’t be normal! Even those of us with many years of experience put the molt out of mind, until one day we walk into the coop and seem to be wading through feathers.

The onset of the molt signals the end of the laying season. Molting hens stop laying because they need to put all of their energy into growing feathers. Then, by the time they’re back in full plumage, it’s winter when there’s less light, and it’s cold, and so they continue their break from laying until spring. Here in New England, egg production slows in late August and resumes again in February. Despite the molt, there’s always a hen or two who lays right through the molt, and some hens molt quickly and resume laying with barely a break. The eggs from those hens will be precious!

Molting is a messy, lengthy, disruptive event. Each chicken has about 8,500 feathers. Some birds will lose all of them, seemingly at once. It’s as if the hen is a cartoon character that sneezes and then finds herself embarrassingly naked. More often than not, it’s a patchy affair, with some bald spots and other areas looking raggedy. A few chickens never look scraggly and you can tell that they’re molting only by the evidence of their feathers on the ground. Like the leaves falling in autumn, the a flock doesn’t molt at the same time or pace. It can take a several months for everyone to lose their feathers and during that time the coop will look as if there’s been a pillow fight overnight. Every night.

Although books will tell you that all molts progress from neck to back, wing to tail, your own hens will likely be the exception to the rule. Lulu, who did everything more dramatically than the other hens, lost her tail feathers first, until all were gone but two. She looked like she was wearing one of those costume Indian headdresses that used to be sold at five and dime stores. That lasted for a couple of days, then more feathers dropped until she looked like a discarded, worn-out child’s toy. New feathers first appear as pointed quills. When Lulu’s feathers were growing back in, she looked like a crazed porcupine.

Some chickens don’t molt until it’s truly cold out, and their owners worry that they’ll literally freeze their butts off. This is not a cause for concern. There’s no need to hang a heat lamp in the barn. Somehow they’ll stay warm.

Your poorest layers will be the first to molt, and their molts will take the longest. In days past the birds that molted in the summer were the ones that went into the soup pot as only the best layers were kept through the winter. I take note of who molts first, but my hens get to stay around, grow new feathers and enjoy a break from laying. As much as I miss the eggs, it’s good for the hens to have a few months for renewal. For me, it’s a reminder that my hens are not egg laying machines, and that even a basic commodity like an egg is a product of a complex animal, linked to the cycles of the natural world.

Molting chickens act differently; they often become subdued and less active. Molting is probably uncomfortable and tiring for them. Again, there’s no need to worry – they’ll perk up when the molt ends.

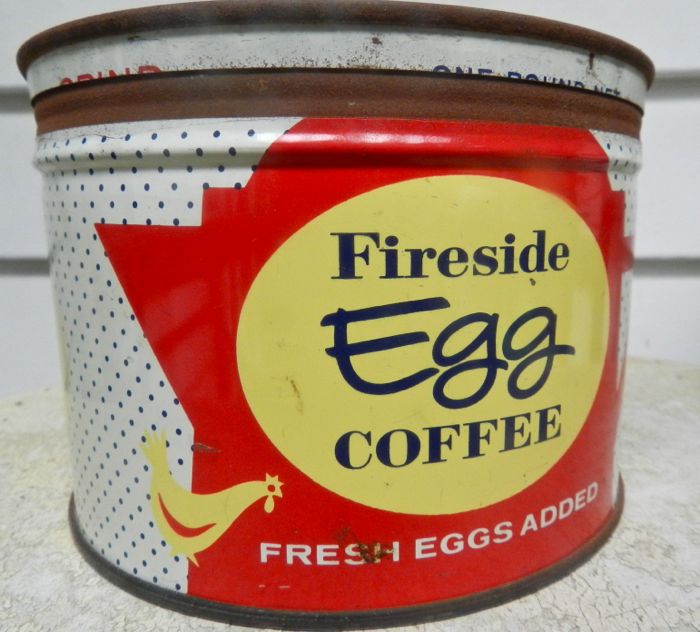

Feathers are almost pure protein, so it’s good to add extra nutrients to the diet during the molt. In days past, farmers added bone and bits of meat. These were ground on site, and you can find antique tools for this task on eBay and at flea markets. Meat attracts vermin and predators, so if you do feed it, provide only as much as the chickens can eat up quickly. Also, bacteria and diseases can be transmitted through meat, so only use only that of good quality. Some people add dry cat kibble to their hens’ rations. Since most commercial pet food is made from meat of questionable sourcing, it’s not something that I do.

Bugs are a great source of protein, so if you allow your hens into the fallow fall garden, they’ll clean up pests hiding in the old vegetation and at the same time get the additional nutrition that they need. Hens limited to a small run can be fed any one of a variety of store-bought products. You can buy freeze-dried mealworms, (sold at at various stores packaged for different animals – pet lizards, wild birds, and chickens – but it’s all the same product.) They’re 50% protein and the hens love them, but too many can trigger kidney failure. A teaspoon a day per hen is plenty! Besides, mealworms are very pricey. Hulled sunflower seeds are an excellent source of protein and essential fats, but again, too many can cause kidney failure. Another option is to purchase a supplement formulated for molting pet birds, like canaries. These products are high in protein and the other nutrients needed for feather growth. I gave some daily to Lulu when she was molting, and her feathers grew back beautifully, glossy and thick. Feed stores stock supplements made for chickens. Calf-manna is a brand that’s been around for decades. They make a poultry conditioner that looks like laying hen pellets, but it’s obviously “manna’ by the distinctive anise aroma. They say that the spice helps palatability. When I fed it to my flock, they certainly liked it and came through the molt with beautiful new plumage.

If your hen molts out of season, it could be due to stress. A hen kept from food (from bullying or an ailment) will molt. In fact, factory egg producers use that knowledge to implement an inhumane practice. The CAFOs hate molting, it’s not predictable, uniform or productive, and so they starve their birds so that they’ll all molt at one time. Since starvation has been outlawed in some countries, there are companies working to develop chemicals that will initiate and control the molt. Just thinking about that makes me more tolerant of my hens’ cycles.

As far as what to do with all of those feathers… I save the longest and prettiest ones for dried flower arrangements. Some I give to children during school visits. The feathers make good cat toys, too. All of the rest go into the compost.