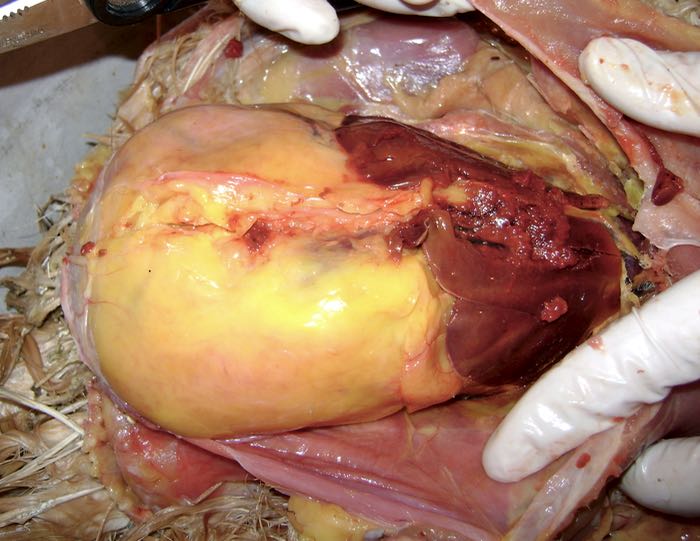

WARNING: graphic photograph

A leading cause of death in caged laying hens is fatty liver disease. Also called FLHS or Fatty Liver Hemorrhagic Syndrome, it’s a disease in which the liver becomes compromised and eventually hemorrhages. Fat can no longer be processed and it is deposited on the organs and in the body cavity. Although the way that we care for our backyard hens seemingly has little in common with the industrial agriculture model of confinement in small cages and cheap food, our small flocks are also succumbing to fatty liver disease.

This is bad news, because the hens quickly loose vitality and die, but also good news, because it is entirely preventable.

FLHS is primarily caused by feeding too many carbohydrates, usually in the form of corn. This excess energy can’t be processed – basically the liver gives out trying. You might be feeding corn and say that you don’t have a problem. This is because unlike caged birds, most backyard hens are getting exercise and can burn some of the excess energy off. Also, caged birds succumb to FLHS because they are additionally stressed by confinement and high temperatures. However, even if kept in optimal conditions, as chickens age, they become more susceptible to the disease. I’ve seen and heard of many cases of fatty liver disease in backyard flocks.

When hens in commercial flocks die of fatty liver disease, it’s because the companies are cutting corners, feeding cheap grains, jamming the birds into cages, and not keeping the buildings clean and dry. Our chickens don’t live under those conditions, but they’re still getting FLHS. Why? The answer is that we are loving our hens to death.

Cracked corn is like candy to hens, and once they learn the sound of a can of corn rattling, they’ll come running. I know, because I’ve trained mine to come, and it’s hilarious and a lot of fun to watch (See video here.) But, corn, or the similar product of scratch grains, is nothing but empty calories. There’s no reason to feed it to your hens. Even “scratch grains” are not necessary to feed. I do have corn on hand for calling the hens back to the run, but I know the danger of feeding too much. Each hen gets less than a teaspoon as a treat and I don’t feed it on a daily basis.

I don’t because I’ve seen this:

You won’t find photos like this on veterinary sites or in research sponsored by the agriculture industry because this is what happens to an older hen with fatty liver disease. Even if you’re not feeding corn, this can happen. Sometimes it’s caused by bread and pasta. Whatever the excess carb, the liver is destroyed and the body cavity fills with thick fat. Often, when a chicken stands like a penguin and looks listless, the hen keeper thinks “egg bound.” That’s rarely the case. More often, it’s this.

But, it’s preventable! Don’t feed cracked corn on a daily basis, and if you do, offer it only as a training treat. Provide lots of interesting scraps from your kitchen, but make sure they’re vegetables and the like, not leftover breads and rice. Give your hens plenty of exercise and sunshine. Give them protection from extreme heat. There are so many diseases that we can’t prevent, but this one we can.

Please share this post with your hen-keeping friends. Let’s get the word out.