A hundred years before the era of cat videos gone viral on the internet, this is what people shared.

Monthly Archives: April 2014

Sweet Clementine

I was not surprised to get the call, yesterday, that Clementine had died. She had been a very sick hen, and when I pulled her back from the brink, (read about that here) I didn’t expect her to go on to a long life, but I had hoped for more than the two weeks that my care ultimately gave her.

Still, she had been able to rejoin her flock, get love from her best friend, Lisa, and comfort the residents of the nursing home.

Clementine died peacefully in her sleep. Few hens pass so easily, and so that was good, too.

I did a necropsy, which confirmed what I had deduced. Clementine was an internal layer. Instead of the yolks progressing down the reproductive tract, and forming eggs, they were dropping into the body cavity. This is not uncommon. Sometimes a yolk misses the fallopian tubes, and so drops into the body cavity, where it is reabsorbed, and so the hen is ill briefly, and then she recovers. Sometimes the fluids in the body cavity become infected. Dosed with antibiotics, the hen might stabilize, the unformed eggs solidify, and she can go on with her life. In other cases, the the internal laying turns into peritonitis, and that kills the hen. Often, when the internal laying isn’t severe, my spa treatment of an epsom salt soak helps to move things along, revitalize the hen’s systems, and she goes back to laying normally.

The necropsy on Clementine showed something that I haven’t seen before. Clementine was egg-bound. A soft-shelled egg had become stuck in the reproductive tract. It was so far up that palpation would not have detected it. It must have formed in the shell gland (which is near the exit point) and then, instead of moving out, backed up. Over time, yolks and whites progressed towards this stuck egg, surrounded it, and formed a mass. This effectively blocked her tract, and so new yolks, being released from the ovaries, had no place to go but into the body cavity. Her abdomen was a solid mass of yolks. Poor girl.

It is amazing what a hen can live with. Clementine, up to the end, was eating and drinking. The necropsy showed a full gizzard and a healthy amount of muscle. She had rejoined the flock, which had accepted her. She was weak, but otherwise acting normally. In Clementine’s case, saving her so that she could have a last two weeks was the right thing to do. But, this is rarely the case. Clementine revived, and was eating and functioning on her own. A hen that is listless and can only eat gruel, one that has to be kept isolated and in a cage, should not be kept alive. When a hen acts like that, something disastrous has happened inside of her. Something that cannot be fixed. Having done over twenty necropsies on such birds, I can tell you that if the spa treatment, TLC, and (depending on the symptoms) antibiotics, don’t improve things in a day or two, that heroics and babying the hen, actually causes suffering. I’ve come to the conclusion that if the hen can’t live a good chicken life outside with her flock, then she should be euthanized as soon as she stops being able to eat on her own, or at least be allowed to pass on without intervention. When a hen doesn’t want to eat, she’s sending a very strong message in the only way she can. It’s up to us to respect that.

These decisions are hard. They go against the grain of us wanting to do anything and everything for animals we love. But, letting hens go is as much of a part of backyard chicken keeping as collecting eggs is. If you have a small flock, you will be faced with these decisions. I’ve discovered that with these animals there are few grey areas. Either they are well, or they are not. Either they will revive with sensible care, or they won’t. And if they don’t rebound, it’s up to us, as their caretakers, to not let them suffer. As evidenced by Clementine, a hen can live for weeks and even months, with things going catastrophically wrong inside of her. Clementine, amazingly, retained a decent quality of life to the end. But, if she hadn’t, prolonging her life would not have been a kindness. Having seen what I did in the necropsy, I am glad that she passed quietly in her sleep.

I will be discussing this case and others in my Advanced Chicken Keeping Workshop. For more information about that and other programs, go to my Upcoming Events page.

Clever Goat

Two days ago, I looked out of the upstairs window and took a double take. There was a goat on the lawn.

Notice that the barn door is closed. The paddock gate is closed. And yet, Caper is on the lawn. His brother, Pip, is relaxing on his bench inside of the goat pasture. Did Caper dematerialize from one side of the fence and materialize on the other? Did he say Beam me up, Scotty! and get transported to the side of the fence with the green grass?

Steve investigated. The gate has two chains to keep it shut. The bottom one was off the hook.

Yep, Pip figured out how to unlatch the chain and squeeze through the gate. (Notice that the chain on the top is still on. Notice the size of Caper’s belly. He must have defied some law of physics to do this.)

Recently a study made a big splash in the news. It announced that goats are intelligent! Those of us with goats read the study and shook our heads. The test that the researchers presented the goats was easy-peasy. It was like asking an MIT mathematician to recite the times tables. Obviously, the researchers hadn’t ever kept goats.

Steve got Caper back in. I secured the gate with what I had on hand. You have a lot of extra clips and carabiners when you keep goats.

There! I said, Caper can’t get into trouble now!

Never, ever say that about goats.

That night, Caper discovered that if he bangs on the stall door, that a loose wire will fall off of the wall. Nice toy.

Good to chew.

Luckily, it was not high voltage.

Notice that all of these stories are about Caper.

Pip is the gentleman.

He says that he deserves some peanuts for being so good. He does. I also think that Caper deserves peanuts for being so clever. Those researchers could learn a thing or two from him.

A Thorough Coop Cleaning

I’ve cared for numerous animals, and so I can tell you that it is the modest chicken that makes a mess of every inch and nook and cranny in your barn. These birds scratch and shred anything that is underfoot. They produce copious amounts of manure, which gets turned into dust by their scratching. They shed keratin from their feather shafts which is also minced to bits by their feet. Mix this powdered manure/bedding/feather material together (as they do, what with their dinosaur feet grinding everything into bits) and what you have is a fine, sticky dust that coats everything.

For the sake of my bird’s health, and my own, and also to simply enjoy being around my flock, I keep the coop tidied up. I skip out manure twice a week. Every weekend I do a more thorough job (to read about manure management read this post.) I sweep down cobwebs with a broom. My barns are very well ventilated with fresh air, and sunlight streams in. Still, at the end of the winter, dust has accumulated.

It piles up in the windowsills.

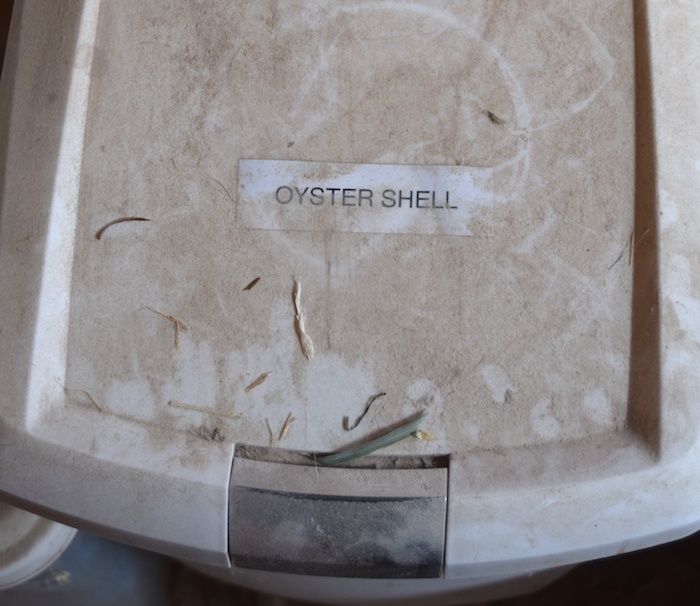

The dust is so thick that it almost obscures the labels on the storage cans.

Cobwebs drip down.

This is not just unsightly. Cobwebs and dust hold viruses and bacteria. The dust itself impairs breathing. It all contributes to respiratory disease. So, at the end of the winter, which is finally now, I do a thorough coop cleaning.

All of the bedding is shoveled out.

Notice that I wear a dust mask. As well maintained as my coop is, that protection is necessary.

The old bedding is dumped into the manure pile at the side of the pumpkin patch.

I sweep every last bit up. See all of the dust that was under the bedding?

Next, I get out the shop vac. I even get on a stool to reach the cobwebs that have been blocking the cupola and the soffit vents in the eaves.

I wipe down all surfaces, and wash the windows to let the sun in. The storage area is tidied up, and forgotten bits and bobs that accumulated when it was too cold to bother with them, are stored properly or thrown out.

I don’t wash the walls. This is not a disinfecting cleaning like a commercial barn does between selling off old, and bringing in new stock. Not only is it still too cold, but I need to get the hens back into the barn. A washed barn remains damp for days, and that’s not good for the chickens.

Lastly, I put down fresh bedding. I used pine shavings for years, and it’s excellent. Recently, I’ve switched to Koop Clean, which is chopped hay and straw with a desiccant mixed in. The chickens stay active looking for tidbits in the hay, and it keeps the coop very dry and sweet-smelling.

It’s a lot of work to do this sort of thorough end-of-winter coop cleaning, but it is ever so satisfying. The air in the barns feels fresher, and it’s wonderful not tot kick up a puff of dust when feeding the hens.

The animals always come first. Now that their home is readied for springtime, I can get into the garden. I’ve already begun raking the leaves out from the perennial beds. I surprised a toad! Springtime is definitely here. The last bit of snow will be gone by the end of this week. I have a good deal of satisfaction knowing that my coops are ready for the warm months to come.