Only one of the seventeen hens in my backyard is laying.

Twiggy.

She is a two-year old White Leghorn. Twiggy was the first of a batch of twenty-five chicks (that arrived here in the spring of 2013) to lay. She produced her first egg at the age of 17 weeks. She then laid one egg a day for an astounding two weeks straight before taking a 24 hour break and resuming production. She laid all through last winter, not daily, but enough so that there was always a white egg in the refrigerator.

Twiggy is now 20 months old. All of her flock mates are finishing their molts, which is when a hen drops all 8,000 of her feathers and grows new ones. All birds molt. Chickens molt once a year, the first time that this occurs is at the end of their second summer, at about 18 months of age. Some of my hens molted way back in August and now have perfect plumage, which will keep them insulated and warm through the winter months. Some of the hens are still bare in patches, and their new feathers are just coming in, making them look like porcupine-bird hybrids. Twiggy is the only hen in my flock to not yet even begin to molt. When a hen molts, she ceases to lay. Twiggy is not ready to stop yet. But, look at the tip of Twiggy’s tail. Those are old and worn out feathers. She has got to stop laying. I’ve told her so. She’s not listening.

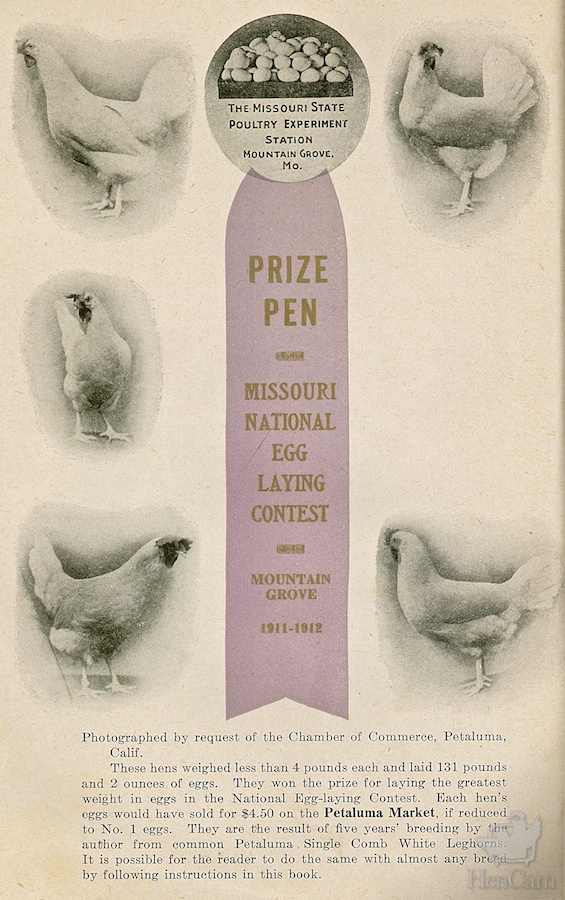

A hundred years ago, Twiggy’s breed, the White Leghorn, transformed poultry farms. Instead of being marginal animals, cared for out the back door by the farm wife, chickens became the centerpiece of a farm’s business plan. A farm with a large flock of leghorns could turn a profit. This book, published in 1913, is typical of the poultry boosterism at that time.

Instead of laying 90 eggs, like a typical utility chicken of that time, a purebred Leghorn produced more than 200! The evidence from egg laying contests was touted in books, magazines and through government pamphlets.

Over the years I’ve had four bantam White Leghorns. They look like miniature versions of the standard-sized birds. But, like most bantams, they aren’t particularly productive. Twiggy is my first large White Leghorn, and she has more than lived up to her breed’s reputation for being amazingly prolific layers. I keep chickens not only for the eggs, but because I also happen to like hens. Personality is important to me, and I’d heard that Leghorns were “production” birds and not all that interesting. I’ve discovered that that’s not true at all – at least not if you have one Leghorn in a flock of seventeen birds of a variety of breeds. Twiggy is active and a tad flighty, but also personable, and her floppy comb makes her look a tad ridiculous. She’s curious and bold and is a fun foil to the more staid, heavier old-fashioned hens. Leghorns are not long-lived birds, but I’d like to have Twiggy around for a few more years. It’s important for her health that she rests and rejuvenates during the ten-week process that is the molt.

It’s time to molt, Twiggy. Take a break!

She says that she will when she’s ready.