After almost two decades of chicken keeping, I finally had a case of bumblefoot in my flock. Sometimes bumblefoot is due to getting a splinter or a cut in the bottom of the foot. Typically, bumblefoot occurs when a heavy hen injures herself jumping off of a roost. All of this leads to a infection inside the pad of the foot which results in severe swelling and pain. If the injury isn’t attended to, the infection can spread up the leg and kill the bird.

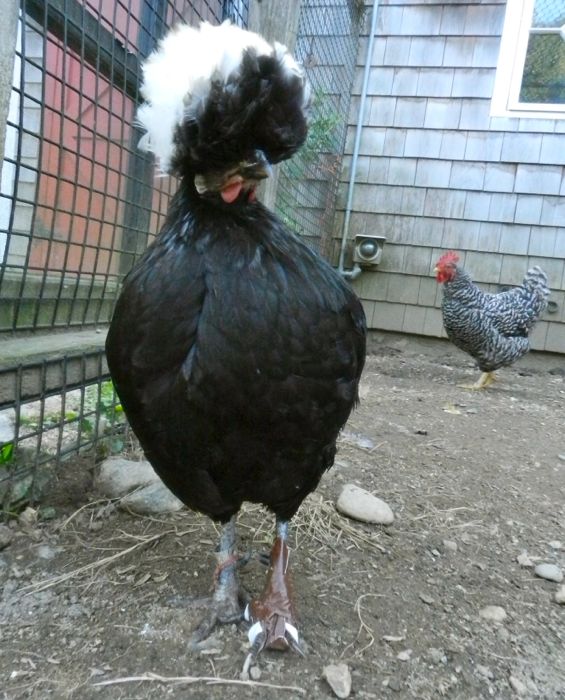

Of course, it wasn’t one of my heavy and older hens that got bumblefoot. It was lithe and skinny Tina, which shows that there’s always an exception to the rule. She wasn’t limping too badly, but the swelling was hard to miss.

Inspection of the underside showed a scab, or plug.

A trip the vet would have cost several hundred dollars, which in all honesty, I am not willing to spend on Tina. Besides, the travel and anesthesia would have been stressful for her. I decided to take care of this on my own. I got out my chicken medicine kit. I pulled on some disposable gloves – the infective agent is usually a staphylococci bacterium, something that, if accidentally ingested, could do me harm.

No one was home, so I had to do this one-handed. (Which also limited the ability to take photos during the operation!)

I held Tina in one arm, snug against me, holding the foot with my left hand. In my right hand I wielded sharp tweezers. Wit a bit of twisting and digging, I pulled off the plug. I was surprised that only a trickle of gunky liquid oozed out. I squeezed. Nothing. I inserted the tweezers into the now open hole and felt around. Meanwhile, Tina was more annoyed at being held than at what I was doing to her foot. She only squawked once during this entire operation. The tweezers found a hard solid mass which I grabbed with the sharp tips and pulled out. It was a lump the size, shape and hardness of a peanut. With more probing and poking, I pulled out a second one. My guess is that these are a combination of infected fluids and tissue that solidified, rather like a pearl in an oyster.

I rinsed out the foot with running water. I generously squirted a broad spectrum antibiotic ointment (purchased from the vet for an injury some time ago), into the hole. I covered the pad with a strip of clean bandage, and held it all on with duct tape. I used dark brown duct tape – the silver encourages pecking. I put Tina back into the pen with the other hens. After a couple of funny struts and a peek at her bandaged foot, she walked off, looking as normal as Tina ever looks. That evening she roosted with the others.

I changed her bandage the next day, and although there was still some swelling,

the foot looked deflated. I bandaged her up again, and even with cotton and duct tape attached, Tina walked without hesitation or limp.

Two days later I removed the bandage and soaked Tina’s foot in a warm epsom salt bath. (I used a half-cup of epsom salts in the tub.) I did this to draw out any remaining infection and to deep clean the foot. It was easiest to soak Tina, too, and she seemed to like it. She settled right in.

There was still some swelling in her foot, and the hole was open so I poked around with the tweezers, but didn’t find anything nasty inside.

I squirted in some more antibiotic ointment and bandaged her once more. That bandage fell off two days later and upon inspection, the foot pad appeared healed. I let it be.

A week later the foot seems healthy again. Compare it to the other foot. There’s nothing pretty about chicken feet, especially on older hen’s dirty, scaly, lumpy feet. But, having seen this foot ballooned up with infection, it looks darn good now.

I’ve talked with others who have more experience than I with bumblefoot. Some chickens get recurring infections. Some, despite surgery, never recover. I hope that I don’t see a case for another two decades. But if I do, I hope I’ll be as successful treating it as I was this time around.